The Scott and Shasta Rivers were once some of the most productive salmon habitats in the Western United States. The Scott River’s incredible gravel beds and meandering flows were perfect habitat for salmon to create their nests and spawn. The cold spring flows that are the heart of Shasta River provided ideal temperatures for coho and chinook salmon to lay their eggs and grow into the smolt that make their journey out to the ocean. Engrained in their biology, these fish are drawn back up the Klamath to their natal streams when it comes time to spawn. However, the fish that make this journey are swimming into a very different environment than their predecessors did 170 years ago.

For almost two centuries, water in the Scott and Shasta Valley has been taken from the rivers for grazing and agriculture. As a result, flows routinely dry to less than belly-scraping levels, preventing salmon from even entering these important tributaries, let alone thriving in these streams. Run-off from irrigation has raised water temperatures to near lethal levels and what was once some of the most productive salmon habitat is now barely able to support individual fish, let alone healthy populations.

These fish are not only ecologically vital as keystone species, as they transport nutrients from the ocean inland and vice versa, they are the cultural center of many tribes that call the Klamath River home. Yet they continue to decline, and if nothing changes, these fish will be extirpated from these river systems. This year, numbers were so low that no salmon were served at the Yurok Tribe’s annual salmon festival in an effort to support the weakened population.

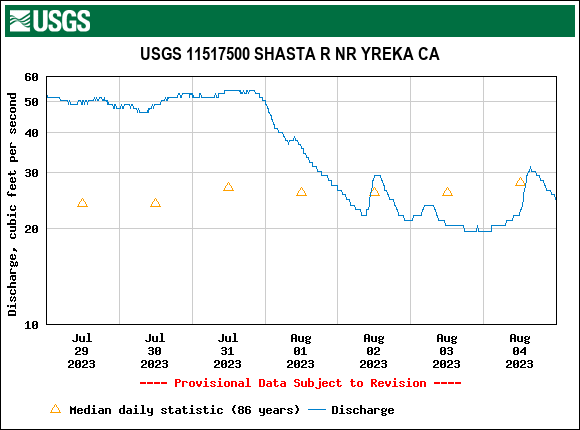

The intense drought of the last few years forced the State Water Board to establish emergency regulations to ensure there was enough flow in these rivers for salmon to survive the extraordinarily dry years. However, emergency regulations are crude. They are designed to prevent catastrophe, not to promote success, and they last only for a year. Yet even those crude emergency regulations were necessary, as when they expired in August, flows in the Shasta River dropped by half.

To protect these important fish and their habitat, California Coastkeeper Alliance has collaborated with tribal groups and other environmental organizations to compel the State Water Board to establish permanent instream flow regulations for these rivers. These requested regulations would require a minimum level of flows and temperatures to be met in both watersheds at key times of the year to ensure that these salmon are able to recover, not merely survive. The Karuk Tribe and other Petitioners have already submitted a petition for these regulations to the Water Board for the Scott River, and CCKA plans to submit a similar petition for the Shasta River in the near future.

In response to the Karuk petition, on August 15th, the Board held a hearing on the issue of minimum instream flows for the Scott and Shasta. The hearing was contentious, and public comment and expert opinions were heard late into the evening. Due to compelling advocacy and science, at 11:30 that night, the Board committed to readopt the emergency regulations they had let expire.

This victory came at the heels of persistent advocacy. But the process of developing permanent regulations will take years and has yet to truly begin. California Coastkeeper Alliance will continue to work toward the goal of recovering these waterways and protecting the salmon in the Scott and Shasta Rivers.

Stay informed about our efforts to protect California’s waters by subscribing to California Coastkeeper Alliance’s monthly newsletter, becoming a lifetime member, or following us on social media: @CA_Waterkeepers.

Staff Attorney Cody Phillips advocates for statewide policies that protect water quality and access to clean water throughout California.